CFB '23 - Week 14 Preview

Three contenders battle for it all on a dark, chilly Saturday night

This Is It

A Three-Horse Race On A Chilly Saturday Night

A Saturday (and Friday night) Of Big Favorites Underlies Last Push Between Olsen, Bertolina, Goss

Potential Scenarios Could Hinge On Bertolina’s Amount

When The Demise Of A Conference Affects Someone You Know

The Final Obituary (Feat. Lil Wayne)

This is the best time of the competition. All the jockeying comes down to this weekend.

We should be pouring a holiday cocktail, handicapping the final week’s games, and fostering that once-a-year type of anticipation.

We are. And we will.

But before we get to that celebration, and the analysis of its concomitant potential wagering scenarios, a story:

Last week, the Commish wagered his largest amount (not saying much) in some years on Auburn +3. This was an alternate spread on the Iron Bowl that, if bet and won, paid out far more (+270) than the real spread, the much more attainable Auburn +15.

Auburn was leading by four points with seconds remaining, when Isaiah Bond caught a 4th and 31st Hail Mary from Jalen Milroe in the back of the end zone. Alabama went up by exactly three, and your boy’s winnings vanished in a blink after Auburn had covered comfortably for most of the game.

At the immediate aftermath of Bond’s catch, the Commish’s neighbor, Wayne, was walking his horse of a poodle dog outside HQ’s front window. Wayne is probably 70, likes to write complaint letters to the local HOA as well as Amazon.com on account of its inconsistent and inaccurate delivery practices, and is bracingly white. He has a master plan for every house in the neighborhood to go in together each winter on a snowblower, but executing the plan somehow always slips out of reach. He once donated to me a string of extra Christmas lights that I made every effort to deny receipt of, and they now collect dust in my garage.

It is for these reasons that I have chosen to refer to him throughout my and Mrs. Onion’s daily lives exclusively as Lil Wayne.

Lil Wayne is the is the most die hard Oregon State fan I have ever met. I do not know how he acquired my phone number, but one day I received a text about Oregon State football from an unknown area code. Now, we go back and forth regarding all things Beavers. It is the only subject we discuss, other than the snowblower.

Obviously, this has been a hard year for Lil Wayne.

Much of his fandom owes to the fact that he played defensive linebacker for the Beavers in some prehistoric decade. He is of a different era. He is more, shall we say, pure. And crotchety. Lil Wayne is one of the good guys.

At the time he passed by my window I was despondent about my lost winnings, just doing and being completely the worst. There is something uniquely repugnant about the “poor-me” act of a lost bet that exceeds the audience not caring. I still can’t articulate this repugnance, but in this moment, I was nearing this territory.

Not knowing he was tweaking me at the wrong time, he shouted through the glass window with classic Lil Wayne timing, “who’d ya have today?” So I went outside and told him.

I felt ashamed as soon as I finished relaying my bet story. For him, this was the afternoon after a sad Civil War loss, the week after a heartbreaking loss to Washington, the year of his former program getting left for dead.

I held a piece of paper that wasn’t worth anything any longer, and it was inconvenient to me. He held actual pain.

And as if the rats weren’t already scurrying off the Oregon State ship, the news broke that morning that Beavers coach Jonathan Smith was leaving the program for Michigan State, not exactly a white rose of a program or athletic department.

As one Onioner put it, the move sent “a clear signal to everyone, but especially OSU and WSU players, that that situation in Lansing is preferable to whatever is going to happen to the Pac-2.”

Snapping out of my sad sack reverie, I noted to Lil Wayne my disbelief that first the Big Ten not only raided Oregon State’s fellow teams – it raided their coach.

He looked at me quizzically. I repeated the condolences.

He hadn’t heard the news yet. He pondered. Then, silently, he turned for home.

An hour later he texted me back saying that he verified the story, and broke the news to his (what one can only assume to be legendary) group email thread full of his former ancient teammates. They were all shocked.

“This is the nail in the coffin,” he wrote. “Players will all leave. Mass exodus.”

Few have openly confronted the fact that Smith’s move runs deeper than, “the team won’t play in the Pac-12 any longer, and they’ll need to hire a coach.” It runs potentially all the way down to, no conference, schedule, no coach …transfer portal… no players. Then what?

At best, you scrape together some two-stars and eager young coordinators, and serve up a this-is-too-hard-for-the-diehards-to-watch product that is a shell of its former self, like if those accustomed to old school Sports Illustrated had their eyelids peeled back and were force fed the new A.I. Sports Illustrated.

At worst, do you even have a program?

Imagine seeing a family and a tradition that you and hundreds of thousands of others were a part of for over a century, a program you played for, get shuttered (literally or figuratively) purely because other people wanted more money.

Now, imagine if a college football program in a more heavily populated area, or with wealthier alumni, or with more TV visibility, or in a more favorable time zone, was death-by-a-thousands-cuts’ed in the same way — by being deserted by its peers, then slowly choked off from the system that forms the lifeblood of 21st Century collegiate athletics. Imagine the shit-throwing that would occur. The outrage. Think how loudly all of those very important TV and radio and podcast personalities would speak, how strained and whiny their incredulous voices would be.

Imagine if it happened in the South.

When the Malaysian Airlines plane went missing in the Indian Ocean in 2014, there was an oft-repeated line from media and commentators: “Planes go up, planes go down. Planes don’t vanish into thin air.” The subtext, of course, was that we can’t act like a missing plane is normal.

The same goes for Power Five football programs.

Yet, now, Washington State and Oregon State are the closest examples the sport has ever had to a Power Five team - at least, one that didn’t do anything wrong - disappearing.

And we’re all just sitting around and watching it happen. Like it’s normal.

It’s not normal. It’s criminal. If it happened to your school, you’d be in disbelief.

But it didn’t happen to your school. It happened to Lil Wayne’s school.

And so we dedicate this final week of CFB Onions 2024 not to the whimsical hazard of a lost bet, but to him.

Who Wants To Go First

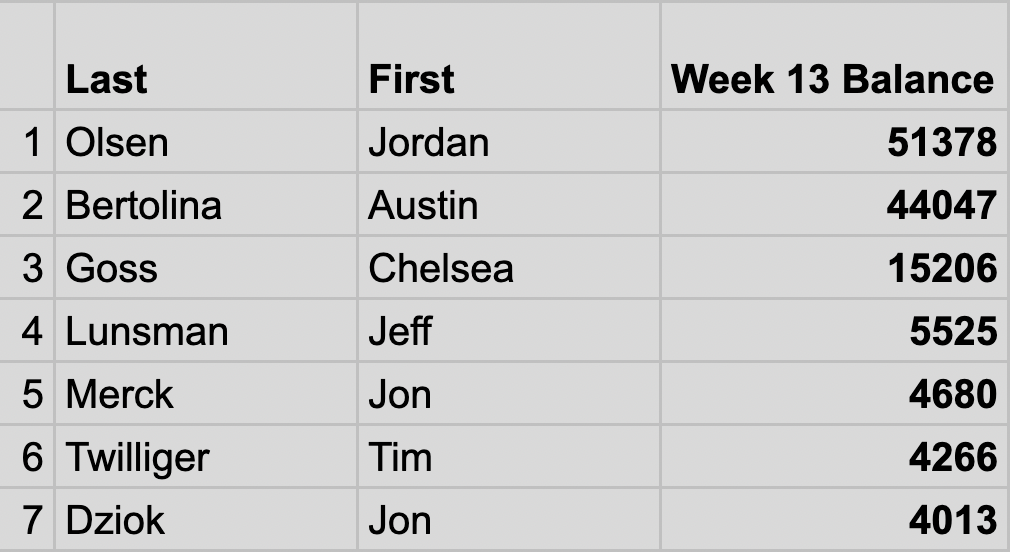

We are most likely, but not for sure, in a three-horse race for the title this weekend.

We’re not saying that Lunsman, Merck, Twilliger and Dziok have no chance of winning. But it does seem highly unlikely.

In order for any of those four to take home the championship, Olsen would have to wager at least 40,000 Onions if not more, lose them all, Bertolina and Goss would also have to have seismic losses, and then one of those in 4th-7th would have to go all in and win.

It is highly improbable that Olsen would wager that much with a 7,000-Onion lead in the final week, because by wagering too much, he risks losing and exposing himself to lower-ranked people catching up to him with all-in wins. As detailed last week, the magic number for Olsen to wager in order to guarantee that, with a win, his balance exceeds a winning Bertolina all-in, is almost exactly 36,000.

Perhaps a larger risk for the top three — and a bigger opportunity for Nos. 4-7 — is one of the top three being disqualified entirely because they tried too long to out-wait the other two competitors, and the timestamp on their submission is after 9am PT on Saturday morning.

In that latter instance, all bets are off, so to speak. As such, we do not dissuade anyone in the Nos. 4-7 realm from going all-in (what do they have to lose, anyway, other than a Top 10 finish?)

Meanwhile, as addressed earlier this week, we anticipate the surviving Goss to be going all-in with her 15,206.

This leaves the key variable amongst the top three as our man in the middle: Austin Bertolina.

Scenario 1:

Bertolina Submits First, Olsen Submits Second, Goss Submits Third

This is the same order of submission that occurred last Saturday in the minutes leading up to the deadline.

In this, the most straightforward example, Bertolina is chasing Olsen in an out-and-out sprint to the finish. Absent knowing what Goss or Olsen are doing, we don’t anticipate a scenario in which Bertolina submits first and doesn’t go all-in. Doing otherwise would likely expose him to too much counterparty risk. (That said, we have no inside information, and the choice is purely Bertolina’s. It’s his rodeo).

Thus, we assume that Bertolina wagers his entire 44,047 on Team X. If he wins, he has a balance of 84,130.

The easiest thing for Olsen to do after he sees Bertolina make this wager would be himself to wager the necessary 36,000 amount on the same side of the same game as Bertolina (a practice known as “tailing” that is increasingly controversial in Onions circles and that we might not allow in coming competitions).

Olsen can only do this, however, if there’s time left before the 9am PT deadline on Saturday to see Bertolina’s pick, go to the Week 14 form, fill out his pick and subsequent information, and input the correct amount to wager.

If Olsen is successful at this, then Bertolina would be prevented from winning the competition, because if Bertolina loses his bet, he has no balance and is out. And if Bertolina wins his bet, then Olsen also wins his bet, and Olsen will end with a slightly higher balance than Bertolina.

In this scenario, Goss would not necessarily need to go all-in in order to win the title. If Bertolina and Olsen both won, Goss is out of contention anyway. If they both lost, Goss would only need to surpass the balance that Olsen has remaining after his 36,000 loss, or 15,378.

Goss sits in third at 15,206. None of the contestants below her can go all-in, win, and surpass this number.

This means that, fascinatingly, if Bertolina went all in and Olsen wagered 36,000, and both wagered on the same team, and their shared side lost, Goss may as well wager the 300 Onion minimum.

Winning that 300 Onion bet would net her 273 more Onions, and take her final balance from 15,206 to 15,479, beating the 15,378 that Olsen has remaining.

There is a scenario in which Bertolina, going first, only wagers, say, 15,000. This is the largest amount he could wager while guaranteeing that, even if he lost, a Goss all-in from below still wouldn’t catch him.

One might criticize this approach as “playing for second place” until you consider that Bertolina might try this tactic by hitting submit at 8:59 and 59 seconds.

In this gambit, Bertolina would stare Olsen down until the very end in a game of chicken, ensure that Goss couldn’t catch him no matter what Goss did, and bank on the fact that Olsen would be disqualified by waiting too long to see what Bertolina was up to, and not submitting in time.

That’s a very risky game to play.

If the strategy backfired, and Olsen had any time to submit at all, all that Olsen would have to do is fire the same 15,000 amount that Bertolina fired, on the same team, and Olsen would be guaranteed to win the whole contest no matter how Saturday plays out.

Scenario 2:

Olsen Submits First, Bertolina Submits Second, Goss Submits Third

Let’s say Bertolina out-waits Olsen, and Olsen submits first.

If Olsen submits first, one expects him to wager no more than 36,000 (again, as a caveat, we have no inside information, the decision is fully Olsen’s). Doing so would create a very simple, win-and-you’re-the-champ environment for Olsen.

If Olsen wagered this much, Bertolina would have no reason to go all-in on the same side as Olsen and try to chase Olsen like in the above scenario, because if Olsen wins his bet then he wins the competition no matter what Bertolina does.

Conversely, if Olsen loses, then his balance would be down around the 15,000 mark.

For this reason, we expect Bertolina in this scenario, unable to catch Olsen and banking on an Olsen loss, to wager 300 minimum on any side of any game. Regardless of whether Bertolina wins or loses, his balance would remain around 44,000, and untouchable by any contestant.

Goss would be left helpless in third place, unable to increase her balance enough to catch Bertolina.

However, Olsen could submit first and wager less than 36,000. Perhaps far less. Why he would do this, or how much less than 36,000 the amount would be, remains unclear.

One can assume that, in this scenario, Bertolina wagers a modest amount (no more than 15,000) on the opposing side of Olsen’s wager, allowing the potential swing of a simultaneous Olsen loss and Bertolina win to propel him to the title, while not exposing him to chasing from below.

Were this to transpire, Goss would again be left helpless in third place, unable to catch either of the two potential winners.

Scenario 3:

Olsen Submits First, Goss Submits Second, Bertolina Submits Third

Let’s start from the main starting point as the previous scenario: Olsen wagers around 36,000.

If Goss submits next, she’ll be doing so prior to knowing what Bertolina does.

This is a very vexing situation for Goss. She has to assume Bertolina does something other than wager the 300 minimum (which in Scenario 2, we argue he would do). If she assumes Bertolina will only wager the 300 minimum, then she has nothing to play for, because if Bertolina only wagers 300 he is guaranteed to finish with a higher balance than Goss, no matter what.

No, she has to assume that, for some reason, Bertolina wagers a large enough amount that he exposes himself to her all-in victory.

One feels in one’s gut that she would go all-in.

Bertolina going third now has a clear path: He doesn’t want to wager more than 15,000, which would expose him to losing to a Goss all-in. And no matter how much he wagers and wins, he won’t be able to catch Olsen. The clear position here is to wager the 300 minimum and hope for an Olsen loss.

If Olsen submitted first and did not wager the 36,000 amount, Goss and Bertolina’s subsequent reactions would depend on Olsen’s amount.

Scenario 4:

Goss Submits First, Bertolina Submits Second, Olsen Submits Third

If Goss submits first, then we would expect absent of other information that she would go all-in. Doing otherwise would allow either of the two leaders to wager small enough amounts that, even if they lose, she has no way to catch them.

Going all in and winning would put her at 29,043.

Bertolina in this case knows that he can’t afford to wager more than 15,000 on any game without exposing himself to being passed by Goss’s potential 29,043 — unless he “tails” Goss by copying her wager.

This would guarantee that Goss doesn’t win the title, and that she and Bertolina would rise and fall in lock step.

But how much more than 15,000 would Bertolina wager, when he doesn’t know how much he needs to catch Olsen, or even if he can catch Olsen?

Bertolina could do one of two things here: He could say screw it, and go all in on Goss’s same side. Either he and Goss both win, and he ends up with a final balance of 84,131, forcing Olsen to chase, or he and Goss both bow out.

Or, Bertolina could wager just over 8,000 on any side he feels good about. Why just more than 8,000? Because that’s the smallest amount he can wager, and win, and exceed Olsen’s current balance of 51,378. This would force Olsen to have to win whatever wager he submitted.

The most efficient way for Olsen to do this would be by tailing Bertolina, if time permits on Saturday morning.

All in all, the last few minutes before 9am PT on Saturday will be rife with drama in the spreadsheet.

Godspeed, one and all, into the final, dark night.