The Fuzzy Morality Of Taking What You're Presented With

How All Stakeholders In The Sports Betting, Sports Data, and Sports League Ecosystem Can Think More Realistically About The Policing and Use Of Play-Calling Data In College Football

How All Stakeholders In The Sports Betting, Sports Data, and Sports League Ecosystem Can Think More Realistically About The Policing and Use Of Play-Calling Data In College Football

Show Me A Sign

The Robn proletariat sprang into action this week with the inquiries:

“Where is the Commish on the Michigan stealing situation?”

“Is Michigan’s season over? Bet Harbaugh gets away with it.”

“UM Sign scandal? Your silence is deafening.”

My silence is deafening? Easy. People with a mind for it have a remarkable ability to hear others talk when they aren’t saying anything, earworms tunneling through said minds’ inner plumbing, like an auto-fill function to determine someone’s intent in the most specious, convenient way.

At any rate, this was supposed to be next Wednesday’s email because next Wednesday was going to arguably be the first time this season – when they play someone against whom they won’t be favored by four touchdowns – in which Wolverines-related discussion matters.

But the obsessively-documented allegations against Connor “Ride Those” Stalions demanded the sort of early attention that a circus freak demands.

Someone (before the NCAA started in) hired an investigative firm to investigate Stalions and the Michigan program. The firm gathered evidence. Then it presented that evidence to the NCAA, who snored itself awake and immediately flew 57 people to Ann Arbor for what I imagine consisted of countless hours of handwringing, important-sounding words uttered beneath furrowed brows, and, as is the NCAA’s specialty, little-to-incorrect action.

What the evidence suggests is that Michigan tried to film opponents’ play-calling signs at games. Now, all sorts of threads are being pulled. Little tangles of fabric are unraveling. We’re talking about a vacuum-cleaner side hustle and facial disguises at Spartan Stadium. Everyone’s handling it all with the measured nuance of commentary about the Israel-Palestine war.

The whole furor, the scrutiny over the act of “going rogue” at a college football game, took me back to the not-to-distant past.

The Eyes And Ears

Ten years ago there weren’t many sports betting apps in the U.S. They were restricted to operations within Nevada state lines and they were atrocious. They were like a building with the structural integrity you’d expect if it had been constructed by a crew of plainclothes volunteers in a Bombay slum.

There are many sports betting apps in the U.S. now. They’re proprietors are all over the places where you consume sports. Some of them run OK. Some of them run like Ferraris. These sportsbooks would like you all to bet with them rather than play a nice sweepstakes game like the Robn College Football Contest that your mother would like.

A leading way these sportsbooks make money is by offering in-play betting - i.e. betting that takes place on a game while that game is being played. In-play betting is faster-paced, less predictable, always changing. It is a higher-margin product to offer than betting on games before the games have started. More customers lose money live betting, and because when they do win at live betting the payouts aren’t as good as pre-game payouts.

Watching live betting markets unfold is like watching someone play violent tug of war with a stock price on the NASDAQ, loosely in correlation with events you see in real-time.

Let’s say Michigan leads Purdue 20 to 3 with two minutes to go in the third quarter. The “live” spread on the game -- the estimated outcome at that moment in time -- is Michigan -28.5. Suddenly, Michigan intercepts a pass and returns it for a touchdown, and goes up 27 to 3. The live spread then pops up to something like -34.5, because that last play made it more likely that Michigan wins by more than the previously predicted 28.5-point mark.

Maybe 10 seconds after that, the live spread fluctuates down to -34, then -33.5, and then -33 based on other actions. It’s all very fluid and intoxicating.

In order to form these odds, sportsbooks need to know what’s going on in the game that’s being played. They need to know it before you know it. They need play-by-play, stats, and especially information when someone scores.

In the year 2023, these sportsbooks have the ability to access this information a number of ways, often in the form of buying access to this data from very special companies.

These very special companies pay major sports leagues insane amounts of money for the exclusive right to acquire that data from the league’s sporting events – sometimes through league employees who sit in-venue and tabulate statistics, sometimes via their own employees who sit in-venue and do the same thing – and then to distribute that data to sports betting companies.

And so, sports betting data is multi-billion-dollar industry.

But these very special companies didn’t always used to have relationships with leagues to acquire in real-time the statistical data which is fed into modeling software and spat out as pricing and odds (e.g. Michigan -34.5) that sportsbooks then put in front of bettors, all in half a second.

The NBA, for example, only formed a relationship with its exclusive sports betting data distributor, Sportradar, in 2016, and even then it was to distribute statistics to media companies, not to sports betting operators. Only after the reversal of the federal ban against new state laws authorizing sports betting in 2018 did these data companies get officially ensconced in the live betting data space.

There was a world not long ago when this data had to be obtained by illicit and scurrilous means.

Or, depending on who you ask, just by means.

Use It Or Lose It

Let’s go back to our example of 10 years ago.

There is a mid-sized data company we’ll call Dataco X. Dataco X is trying to get into the live betting data space for U.S. events – meaning they want to both acquire it from those who have it, and distribute it to those who need it.

Sports betting companies in Nevada, the only place where U.S. licensed mobile sports apps accept bets from customers in the U.S., see live betting as the obvious if not vague “future.” But they’re handicapped by two realities. First, Nevada had about 2.7 million people in 2013 and many who bet on sports there only visited the state for a brief time, meaning they could only bet for a brief time. This isn’t a huge audience to invest in mobile technology for, even if it wasn’t transitory. Secondly, the technology behind the handful of apps in the state might defecate if it had to update odds and pricing second-to-second in real time as the events of a game transpired, and also perform all of its regular creaky sportsbook functions.

But Dataco X’s sportsbook customers over in, say, in England? Color them interested. They’ve bet on things for centuries, and because they’re British they also know everything there is to know about everything.

An increasing array of potential U.S. events on which sports betting companies can offer in-play betting to Brits – and Europeans and Africans and Caribbeans and Chinese – is a welcome product differentiator.

So the foreign sportsbooks ask Dataco X to send them some of that, in the words of one of the companies ex-executives, “Sweet, Sweet Crack.”

In order to get the data to sell to the overseas sportsbooks, however, Dataco X can’t exactly go to the Big Ten Conference and ask it they can have the conference’s betting data distribution rights. It wouldn’t even get a meeting.

If somehow it had, Jim Delaney himself would have come down and breathed sweet hellfire and the attendees would’ve scattered like rats. Then, Mark Emmert would’ve rode in on a witch's broom shrieking like a hyena because if Emmert heard the word “betting” at that time he involuntarily transformed into an Angel of Darkness.

This is 2013 and this is the NCAA. Betting doesn’t yet exist because it isn't legalized. The illegal market is a figment of powerful interests’ imaginations, according to the NCAA. There are no corner bookies, no one wearing the green visor in the back of the muffler shop. There are no criminal rings funded largely by sportsbooks. There are no betting websites operating illegally in the U.S. with customer lists in the tens of millions that have devious workarounds for things like accepting credit card payments. No Americans bet large amounts of money with friends in ways that violate federal.

You’re not even allowed to say the word “betting.” If you say it, betting might begin to exist, and then all of those things might happen. “Betting” and its sordid hangers-on might physically instantiate and walk over to an amateur athlete and ruin their life.

To be fair, it has done this for some amateur athletes in 2022 and 2023. But it also did this many, many times prior to any legalized wagering existing outside of Nevada, and when you asked the NCAA about why this occurred, or about how it proposed to help educate its institutions around betting, or about helping put pressure on policymakers to police the illegal betting market, you were met with the cold stare, before the defensiveness kicks in, of an adult unexpectedly caught in a lie.

So in this tenuous environment, what does Dataco X do? It doesn’t talk to the Big Ten or any other league or collegiate conference about anything. It acts. Surreptitiously. It finds its way onto campuses, into games (wait a minute, it's the physical instantiation!), hiring hungry students and arming them with an iPhone, a ticket and $10 an hour to go to Michigan Stadium and record the outcome of every play of the game on their phone.

What yard line the teams are on. What happened on the last play. The second someone scores, the college kids send a new score update.

Anyone watching TV and trying to bet based on what they see has a feed that’s delayed by up to 45 seconds. The kid in the stands is ahead of that person betting. The difference between the guy betting and the kid in the stands is a billion dollars.

If Dataco X couldn’t get a kid to go to every game (there’s a lot of college football in one Saturday, as we all know) they would have them listen to a local radio broadcast, which is far faster than TV, and type out a play by play within a couple seconds to feed the algorithm.

All this, so a machine can do infinite math in half of one second and that number, that -28.5, that flickers enticingly in front of some half-drunk lout in Bulgaria or LatAm (or, um, in any city in America on one of those websites illegally accepting bets from Americans) can pop to -34.5 long before the half-drunk idiot sees the corresponding play transpire on TV.

What About The Children?

So, what would happen to the $10-an-hour college kids when they did this?

Usually, nothing.

Very few people 10 years ago were going around patrolling the stands of live events for this data-recording activity, referred to in the betting industry as “scraping” or “courtsiding.”

This meant that, usually, Dataco X would get mostly reliable data and make money by selling it to sportsbooks. And it got the data for the price of hiring the college kid.

Sportsbooks would offer (by today’s standards, highly exploitable) the corresponding live betting markets and they too would make money.

This was a nice little arrangement. The gears of grey area marketplaces are already quiet; They aren’t any louder when they’re well-lubricated.

But sometimes, maybe when a little too overt of a click-clack was recorded, maybe following a tip by concerned Boomers sat six rows behind in sweatshirts bearing the home team’s name and those light-blue Land’s End jeans you could drive a Buick through the leg of, the kids were caught and escorted out of the stadium.

This begs the question: What is there to “catch” them at? What law or rule did they break?

And here we draw the first parallel to Stalions, of someone tracking publicly available data and feeding it to a company with someone tracking publicly available data and using it to unfairly beat another team in a game.

Both are suspect. Are they expressly illegal? You’re asking the wrong author, but basically, no.

I’m more interested in a separate proposition: Should they be policed at all?

First, both efforts utilized young people, including students of the school to which the event pertained.

According to the Washington Post, the unnamed investigatory firm that apropos of nothing discernible brought all of this to the NCAA’s attention, “presented its evidence to top NCAA officials including photographs of people investigators believed to be Michigan scouts in action — including current students interning with the football team.”

This reminds us of two things: Cheap labor is cheap labor, and there is an endless array of ways to take advantage of young people who are, “just looking to get into the industry.”

Second, both actions constituted a violation of rules. Sure, they are the rules of the NCAA and/or the school that sells the ticket that Stalions/Dataco X bought so that the kid could attend the game. They are not as far as I know rules that are valid in, like, a real court of law pursuant to statute. They are rules in the sense of, like, Walmart won’t serve you if you don’t wear a shirt or shoes in their store.

Per NCAA bylaw 11.6.1, the NCAA actually doesn’t prohibit sign stealing outright. It has prohibitions against in-person scouting off campus of future opponents, and it also prohibits recording play signals given by opposing players.

Per ESPN: “The NCAA received stadium surveillance video this week that a person sitting in the seat purchased by Stalions was using electronics to film a game, which is not allowed under NCAA rules.”

So, if Stalions did what is being alleged, he broke the rules. There is something to catch him at.

But there is also, now at least, provisions by which to “catch” the kids in the stands tracking play-by-play data.

Putting Some (Infra)structure Around It

As mentioned earlier, sports betting in Europe is decades ahead of the U.S. market in terms of track record, and to the extent that whole infrastructures are not just long-since formed around the safeguarding of betting integrity, betting regulation, betting data rights and dissemination – they are accepted as obvious, largely non-competitive, and necessary. They might not always work very well, but fewer people are walking around legislative corridors over there just completely uneducated and or nervous about bodies designed to help safeguard and regulate the betting industry; to create these things, on its face, is natural and necessary whether you support or oppose betting.

But in the U.S., where we are special and have to reinvent the wheel, the formation and purpose of such entities is either the subject of interminable bureaucratic dubiety from state legislators who have little interest in having a cogent conversation about the legal industry, or the urgent priority of nascent groups that see unclaimed ideological land to colonize for commercial purposes.

Football Dataco is not the company from the example earlier in this piece. It is a real company, one in the United Kingdom that exists as a cog in the aforementioned infrastructure.

Its stated purpose is to “protect, market and commercialize the rights to official match related data” of the United Kingdom’s top soccer leagues, including data for journalistic media as well as sports betting companies.

Football Dataco (FDC) is basically a middleman, much like our very special companies sending kids in 2013 to courtside in the stands, except FDC is doing it on the up and up. FDC has the exclusive right to sub-license the rights to a third party to collect or disseminate data from all of the UK’s top soccer matches. In this case, Genius Sports is the exclusive holder of these rights. Genius also has, among many other relationships. It is a giant sports data company, holding among many other relationships the NFL’s official data rights here in the U.S.

It’s all a bit like the scene in Ocean’s Thirteen when Matt Damon tries to pass off his casino-robbing co-conspirator, the tiny Asian man Yen, as a wealthy real estate mogul: “He owns all the air south of Beijing. Try building something taller than three stories in the Tianjin province, and see if his name comes up.”

OK. But is he going to stop me from breathing the air? From looking at it? From throwing objects up into it?

It begs perhaps a more practical question: What happens when the thing you have “exclusivity” over is a derivative of a product that’s not just in front of millions of people, but that the creators and promoters of that product are begging you to pay attention to?

During Genius’ arrangement with FDC, a rival data company put that exact question to the formal test. The data company, Sportradar, (who for reference has NBA, NHL and MLB’s main data deals in the U.S.) sent scouts to collect play-by-play and statistical data at UK soccer matches.

The lawsuits sprang forth.

FDC claims that it identified and ejected around 300 Sportradar data scouts sitting in the stands and “surreptitiously” collecting data at nearly as many matches. Anecdotal recounting of the practice from those orchestrating it indicates that for every scout that was caught, two or three were not caught.

FDC also claimed Sportradar gathered betting data from non-delayed TV feeds, which it wasn’t supposed to be able to have access to. Genius was quick to remind everyone that, hello, we paid not for access to the data, but for exclusivity to all of it.

It claimed that, because it paid a handsome sum to the FDC to have the exclusive right to distribute this data, the data was transformed into trade secrets.

Sportradar, meanwhile, argued that the exclusive agreement between FDC and Genius was unlawful and void as it infringed on competition laws, and that the FDC abused its dominant position in the marketplace.

It also argued that “prohibiting scouts from recording live data which is readily apparent to any spectator … (is) unenforceable.”

Hmm.

The two companies settled out of court in 2022.

As part of the settlement, FDC and Genius agreed to let Sportradar to purchase official sublicensing rights from Football Dataco so that it, too, could sell the data – albeit a secondary, slightly delayed data feed that was far less lucrative. In exchange, Sportradar agreed to stop sending people to courtside the FDC’s soccer matches.

A Special Device In His Shorts

As it wound through the European courts, the U.S. leagues took notice of the case and started wondering if there were people courtsiding at their events.

Sometimes this (both the wondering and the courtsiding itself) happened even before states outside of Nevada were allowed to start authorizing sports betting. It certainly occurred prior to the U.S. leagues having official deals for sports betting data dissemination — though not prior to the creation of their media distribution deals.

At the U.S. Open tennis tournament in 2016 for example, a man named Rainer Piirimets (Rainnniiieeerr? Did you get the Piir-i-mets to build the new house yet?? I imagine his wife yelling to him) was one of 20 courtsiders caught by authorities at the event. He was expelled. Reports of his capture led to a shocking assertion that courtsiders at tennis matches can cloak their data capture and dissemination through the use of “a special device in their shorts.”

He was served with a 20-year ban from setting foot at Flushing Meadows.

He was caught by a UK-based group called the Tennis Integrity Unit (see: infrastructure) that constantly scanned the stands through the use of closed-circuit cameras to observe fan behavior.

The TIU had jurisdiction for integrity-related enforcement over the events sanctioned by many of the global tennis bodies including the ATP Tour and the four Grand Slam tournaments. This would be like if the NBA was sanctioned by FIBA, and FIBA awarded its anti-corruption watchdog efforts to something called the Basketball Integrity Unit, and the BIU flew over from London to patrol every NBA game, but also had many other duties elsewhere at all times.

Most articles reporting on Piirimets’ transgression buried the lede, noting somewhere in muted tones near the bottom that courtsiding was not actually illegal.

And so, Piirimets returned in 2017 to the U.S. Open to once more capture data, violating his trespassing ban. But what, after all, is a trespassing ban? It is just the Wal-Mart shirt and shoes rule and comes with the full force and effect of a scowl. He was again in 2017 found out by the TIU. He was again kicked out of the stadium.

It’s likely, though not confirmed, that he was acting not for a rogue data company trying to get fast play-by-play data for free (i.e. the Sportradar to the Football Dataco’s Genius), but instead for a professional sports betting syndicate who wanted the data faster than any data company would be able to collect and distribute it.

Why? If the syndicate got the data before the data company did, then it definitely got the data before the sportsbooks who received it from the data company. This would allow the syndicate to know what was going to happen on the field before the sportsbook knew what was going to happen. That’s a good recipe for being profitable bettor.

Once states were allowed to affirmatively legalize sports betting in 2018, major U.S. leagues started doing their own versions of the Football Dataco deal — but instead of a third-party company set up to sell the official betting data rights to Sportradar or Genius, the U.S. leagues sold the official betting data rights to Sportradar or Genius directly.

Several states, in response to league lobbying efforts, attempted to criminalize courtsiding as part of their new laws that enacted sports betting. The efforts met with little success.

Meanwhile, there is federal precedent that scoring and statistical data does not fall under the leagues’ copyright protection claims

Without that pesky statutory mechanism by which to deter people, leagues since reverted to putting language on the back of the tickets that prohibits the dissemination of data related to the game in question. This language, the leagues argue, represents the terms of a contract that you agree to when you buy the ticket.

Today, courtsiding still occurs in America. And if there’s ever a place for it in the U.S. landscape, it’s at the collegiate level, where decentralized and enervated bureaucracy reigns supreme, rights maps are overlapping and contradicting, and some conferences are expanding while others are crumbling before our very eyes.

If the allegations against Connor Stalions are true, he courtsided. Just in a different way.

There is cogency in the argument that it’s “different” when a company or an individual does it to make money from sports betting, as opposed to when a team does it to try to gain unfair advantage vs. an opponent.

If a person or company does it, it’s just two parties’ private business deal at stake. Ho hum.

But if a team does it, the integrity of the game you’re watching might be compromised. This is disquieting to even the most cynical college football fans.

There is futility in the moral outrage over Stalions-is-evil vs. Stalions-is-innocent lines of dialogue, because it prevents a more nuanced examination of whether it makes sense to try to police the use of public information in the first place.

This Doesn’t Belong To You

SI.com, which we will tenuously still consider a functioning media organization, published a story lost in the initial chaos of the scandal that illuminated text messages between Stalions and a University of Michigan student.

Stalions confirmed in the text exchange that some time prior to 2021 he, “Stole opponent signals during the week watching TV copies then flew to the game and stood next to [Michigan offensive coordinator Josh] Gattis and told him what coverage/pressure he was gettin.”

The exchange, if accurate, reveals one thing and suggests another. It reveals that what Stalions stole was so public that he did it by, at least partially, watching games on television. It suggests that, as part of what SI.com termed his, “elaborate scheme to place unnamed associates of his in stadiums of Michigan’s opponents,” he was involving students in his efforts to compile his information — why else would Stalions brag to an existing student of the institution about his successes?

We’re more interested in the reveal than the suggestion, though. The part about TV. Stalions didn’t even have to send people (of any age) to games on his behalf in order to obtain the information he needed. He could rip it straight from broadcast — the act of which doesn’t appear to be a violation of NCAA bylaws, in part because it would be pretty stupid to mandate that a team can’t “use” what it sees on TV. All film scouting would cease to exist overnight.

Others in the college football community agree that all you need to do to crack teams’ signs code is a YouTube TV subscription. From WaPo: “‘Anything that happens in the public eye hasn’t gone too far,’ an unnamed coach with Big Ten and SEC experience told ESPN this week. ‘To be honest, I can watch TV copy of two to three games and get everything I need.’”

It’s almost like public information is uncontrollable.

This logic didn’t assuage the non-Michigan Big Ten coaches prior to the punishment announcement against the Wolverines. They reamed out Tony Pettiti for not acting more quickly to address the situation. The subtext: We all know that Michigan is doing this and they’re the villain. Why don’t you do something?!

Hours later it was revealed that someone had presented Michigan, the perp, with detailed evidence that other teams had stolen Michigan’s signs

And so Michigan responds with its own: “Yeah, Pettiti, why don’t you do something?”

The situation speaks not just to the futility of on-demand moral outrage, and of trying yell “stop” to people performing an activity when everyone performs that activity and you have no power.

It speaks to the futility of rules, policies, etc. on the books that prohibit the use of information for certain purposes when everyone already has the information, when that information is in people’s brains.

Are you going to be that earworm that crawls through the passages of the mind and figures out the information holders’ intent and action?

This isn’t Watergate. Teams aren’t sending people to break into fortified offices and rifle through an opponent’s private files. What’s being stolen is on display for 80,000 fans — for TV spectators — as long as they know where to look.

We believe there is no merit in private bodies’ belief that they can enforce how you use information that they’re volunteering to you in the public sphere, because the “use” of information is cerebral. It is a mental matter.

Moreover, we don’t believe it’s different when it’s a team trying to use that information vs. when it’s a private business trying to use that information, nor whether its use is for commercial gain vs. competitive gain.

It doesn’t make courtsiding right.

In fact, courtsiding is definitionally sketchy. We do not offer a perspective to the contrary.

We debate how to handle the betting data in a more realistic way.

Do You Really Want To Pull The String?

In 1996, the NBA sued Motorola. The league alleged that a pre-internet product Motorola developed, which relayed to people real-time NBA stats and scoring information (imagine if you put the ESPN ticker on a pager), infringed on the league’s copyright on the broadcasts of its games and misappropriated league data.

The court ultimately did not find in the NBA’s favor, and its ruling allowed Motorola to market and sell its product because, as it found, the NBA did not have exclusive rights to factual information generated by its games.

The case became one frequently referenced by enthusiasts of the fact that sports leagues don’t have a legitimate claim of ownership over the statistics and data from their on-court products.

This has not stopped leagues from asserting that they have protection over the statistics derived from their member clubs’ events. I would cite specific examples, but several of them have come during in-person interactions with the leagues where large henchmen have stood by the door, glowering, with a billy club in their hands.

(Note: Leagues and individual teams have since softened their colloquial stance to the more watered-down, “we provide the content that allows for wagering in the first place.” When they say that to you, that means you’re supposed to pay them.)

So, let’s pull this string. If play-calling data pertains directly to the contests the leagues believe they have copyright protection over, and to the numeric final scoring result of said contest, and if it is also publicly available during the course of gameplay to anyone with eyes, then why isn’t play-calling data treated by the NCAA, or by any league, like another form of statistical data? And why wouldn’t the NCAA claim ownership (whether or not they’ve been correct in such a claim hasn’t stopped leagues before) over this type of data, as well?

One can hear the objections already:

One potential red-herring is that there is no legitimate media, betting or other public demand or public marketplace in which one can re-sell the consumption of play-calling data. Therefore, the NCAA or others wouldn’t lay claim to it because there is no financial upside for them to do so.

This is willfully ignorant in a very on-brand way. How can one make this argument when micro-betting companies tout the next great “innovation” in betting as markets for whether the next play will be a run or a pass? Or whether the next pitch will be a ball or a strike? And even if one ignores this evidence, who said that the demand for that data had to be public?

A second potential red herring: The only theoretical “customer” of said data is an NCAA institution itself.

Teams purchase videographic and statistical data all the time for analytical and other purposes. Stalions demonstrates they are obviously hungry for play calling data, as well. So hungry that they’re willing to break rules to obtain it. Even if we don’t dispute the fact that the only customer would be teams themselves, why are teams not legitimate customers? Doesn’t teams being customers beat team representatives using underage students to carry out their work, and roaming sidelines in disguise?

A third: Those collecting the data have no idea what the play calls (a four-box with random iconography from pop culture) or play signals (a series of muppet-like gestures) mean, so therefore the collectors would be unable to synthesize any of it into meaningful insights.

That’s OK. The data-capturing companies just need to record what the signals actually are. They are data providers. They are not meaning-providers. The interpretation of the data that is brokered should primarily be left to the end-consumer.

A fourth answer: Well, the commoditization of play-calling data into a statistic, regardless of customer base, regardless of the intelligibility of the data, might lead to no one making visible play calls any longer.

In which case, the college ranks become less college-y and more like the NFL. Is this really at risk? The wealthiest schools are already paying players to get the best talent, and ADs are shipping Stanford and Cal off for multiple weeks at a time to play in-conference foes Virginia, Duke and North Carolina State. That ship has sailed.

The more you peel back the Onion, fewer and fewer of these reasons hold up.

A Note For Charlie

So, let’s extend it even further, like Tom Cruise going from Mach 9 to Mach 10.

If play-calling data is functionally the same thing as statistical data, and if the NCAA or any other league has a longstanding tradition of really wanting you to think that they own and control the rights to it, then why isn’t it subject to the same dissemination structure as other leagues’ play-by-play data (i.e. through an exclusive third-party distributor)?

Why isn’t an entity trying to monetize this play-calling data, as they will surely do in due course with their betting data lest conferences beat them to the punch?

Why is there not the same hand-wringing about the sanctity and accuracy of play-calling data as there is about betting data?

The answer is because teams or anyone else aren’t supposed to use play-calling data, because using it feels like your team cheating against my team, or like my team cheating against your team. Using it feels like it would erode the integrity of everything we’re watching.

It feels.

In other words, it’s because we all have to pretend like it is data that market participants don’t already use, a stance that whether one is for or against legalized betting one must acknowledge represents the same willful ignorance that have led to too-little partnership to combat things that are detrimental to everyone.

And we have to pretend this, even when the data itself is thrown in our face, on our televisions, broadcast to millions.

Doesn’t that seem a bit silly?

Everyone loves to dogpile on the NCAA for actions that, to many, disadvantage individual athletes while being done in the name of protecting athletes.

The crux of those complaints center on the NCAA’s enduring belief - and insistence that you share it - in the myth of amateurism in college sports when clearly, little is amateur about college sports any longer. Any legitimacy to that belief eroded a few years ago with NIL.

The same parallels exist here. The ecosystem of college football is insisting you believe only one or two bad actors steal signs, that those actors can be sought out and punished effectively, that these are complex matters that aren’t discernible to just anyone with a TV connection. Instead, clearly little about this is complex and everyone does it - punishment simply goes to whoever Tony Pettiti is told to shame first.

Just because everyone does an activity, it doesn’t make that activity correct, desirable, righteous, rule-abiding, etc.

But it’s different when 1) the body penalizing the activity is a key catalyst in goading the activity, 2) a critical mass of the ecosystem participates the activity, 3) the activity isn’t easily identifiable and enforceable, 4) the activity involves people’s own mental thoughts and analysis, which you will never be able to conclusively prove result in specific actions.

You can’t stop people from acting on play-calling information they obtain from a broadcast just like you can’t stop a guy from betting $20 at his local bar.

So, ironically, much as the sports betting industry rallied around the cry of, if-you-can’t-beat-‘em-join-‘em-and-do-it-better in their attempt to lobby for the repeal of the federal ban on sports betting, maybe it’s also time to take a look at a framework to commoditize play-calling data.

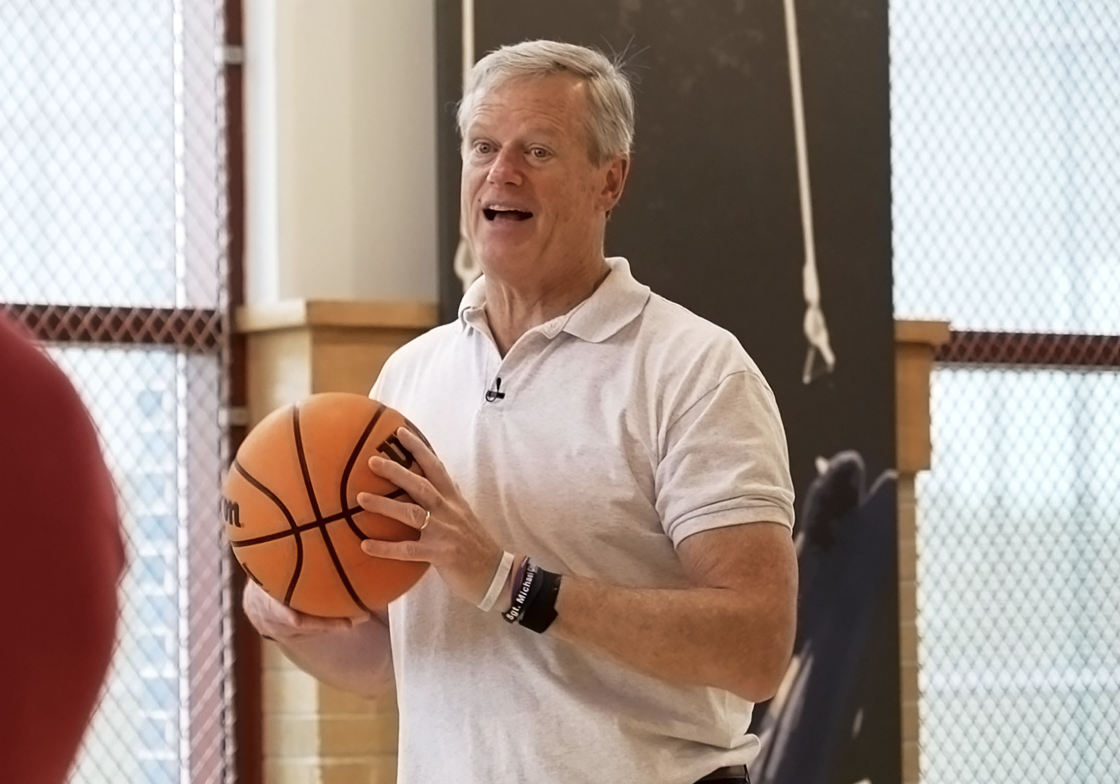

What if new NCAA leader Charlie Baker, a former governor whose cons include being "shocked" by the demise of the Pac-12 and whose pros include being arguably the most sports betting-literate elected official in the United States, created a structure that levels the access to play-calling data, governs its use both at the NCAA level and in legal statute, that gives the live-TV rewind button a break and stops coercing people to surreptitiously record information.

This likely is asking far too much of the wrong organization. And it would be highly imperfect. Again, who “owns” play-calling data and has the rights to sell it, how it’s disseminated, etc., are questions left to far smarter minds.

But doing so can’t be any messier than the creation at the league level of the ecosystem around the “ownership” and dissemination of official statistical and betting data.

We’re sure Charlie Baker will get right on it.