The Encore Of Victim A: The Thread Unspools

The Ippei illegal betting story has expanded to include money laundering at casinos, multiple MLB players who are betting, reality television and dentistry. We are still told Ohtani was aware of none of it. One can only paint so many forced pictures before the pressure of their grip breaks the brush

Highlights

- Ippei was a lone wolf- nope, wait, Ohtani's teammates were also betting

- Ohtani knows enough English to shoot the breeze, but not enough English to preserve victimhood, plausible deniability

- Money laundering 101, and continued implications that Nix and Boyer are connected

- How is Ohtani not guilty of tax fraud?

- Feeding raw meat to the hounds of justice, and by raw meat we mean Tucapita Marcano

In April, as a respite from the last-minute manufacturing of Robn's inaugural Golf Sweepstakes Tournament to satisfy our bloodthirsty and relentless user base, I devoted 7,000 words to a perpendicular subject: the farce that was the handling of the Shohei Ohtani Betting Scandal and associated criminal affidavit, and a number of blatant inconsistencies about the matter that were either dishonestly or insufficiently addressed.

Those who "handled" the incident - Rob Manfred, Dave Roberts, Nez Balelo, Ken Rosenthal, Martin Estrada, the National Association Of Deaf and Blind CPAs - would prefer the incident be referred to as the Ippei Mizuhara Betting Scandal. After all, he's the only one who did anything wrong, and he did everything wrong, and it's exclusively, unambiguously his fault, because that's how stealing $17 million over three years out from under the noses of everyone at Shohei Enterprises Corp. works.

But Ippei is already long-since whisked away to somewhere like Manila, Chengdu or Yangon, and is probably awaiting facial reconstructive surgery in the back room of a convenience store from a non-surgical doctor who moonlights otherwise, stray dogs lurking in the damp, moonlit alleyway outside, his Caymans account burbling to life with the first few modest wires from the involuntary benefactors who will gag him for the rest of his life.

Well, not yet. He'll serve his prison sentence first. Then, this will occur.

But functionally speaking, Ippei is already erased from the face of the Earth (even Uber is firing him), and Ohtani is ensconced as the Face of Baseball. Some form of justice has been served.

The April piece was titled the Ballad Of Victim A, after Ohtani's pseudonym in the affidavit.

This piece is titled the Encore of Victim A because it chronicles several since-revealed chapters in this story. None of the chapters are heartwarming. They involve reality television, licensed casinos laundering Ippei's gambling losses, other betting convictions, and dentistry.

Most of the chapters illuminate the somewhat pervasive nature of betting around Ohtani, his teammates, and elsewhere in professional baseball. It's as if Ippei (and only Ippei!) being accused of placing an average of 25 bets totaling $300,000 (on every sport except baseball! never the baseball!) every day for more than two years didn't paint a pervasive enough picture.

But of course, the horse-blinder style of the accusations and the swift whisking of the affair away to the land of righteous justice were all intended to paint the opposite of a pervasive picture.

It was so un-pervasive that Ohtani was in the dark about Ippei's activities the entire time. Yet "everyone" knew that Ippei was "doing some shady stuff." And Ohtani spoke English with several other people. But not the kind of English where you can hear about any of the bad stuff going on around you.

One can only paint so many forced pictures before the pressure of their grip breaks the paintbrush.

The paramount doctrine from early April is still the paramount doctrine in early June: Ohtani is the Victim. It is Estrada's favorite word, in particular. This was reinforced earlier this month during a press conference that amounted to a choreographed diversion, a sort of Reverse Compliment Sandwich that showed MLB is more than willing to be tough on crime, just as soon as they find some guilty players to punish who aren't in the sport's most elite echelon.

To be clear: Ippei is clearly guilty both of crimes and terrible judgment. He deserves to be punished. I do not assume anything beyond that, including assuming that Ohtani is an evil criminal.

What bothers me about the proceeding is that the handlers mentioned above all refused to let an exploration of the facts of the matter get in the way of a good conclusion from day one. When the facts presented made no sense, no one bothered to ask why, or at the very least, come up with a better story.

The more that people who are not themselves a victim go out of their way to tell you that someone else is a victim, the more you should ask yourself, "why?"

Tyler Tries To Help

The day after The Ballad Of Victim A was published, Ohtani's Dodger teammate Tyler Glasnow commented on the situation publicly.

As if we needed more evidence of a contorted fact-pattern, Glasnow in the same breath exonerates Ohtani - "everyone knew right away that clearly he had nothing to do with it" – and notes that the nature of Ippei's activities were broadly acknowledged - "we all knew early on that Ippei was doing some shady stuff."

The contrast in tone between Glasnow's frankness and the authoritarian scripted party line of MLB messaging is humorous. Moreover, Glasnow's interview reminds us that most baseball players, even one of the sport's very best pitchers, are not in PR, or in the business of selling an entertainment product. They are generally blunt and their bluntness ranges from insightful and honest to inane. Bluntness also breeds a lack of care, a lack of scripting. It is this care and scripting that avoids contradictions that potentially weaken the impact of a desired message.

Glasnow's comments weaken the message of Ohtani's innocence.

Ippei and Ohtani had only been with the Dodgers at this point for roughly a month's worth of spring training games. If we take Glasnow at his word, we are to believe "they all" ("they" assumedly being everyone in the Dodgers clubhouse) knew that Ippei was "shady," except for Ohtani, Ippei's best friend and who Ohtani spent many hours each day with, because Ohtani never knew that anything was wrong.

Thus, in an attempt to support his teammate's innocence, and to hop on the "we're moving past this" train that all of Baseball was riding in early April, Glasnow accidentally re-highlighted the illogic that forms the entire scandal's original sin.

Everyone knew that Ippei was generally shady, yet the person closest in the world to Ippei knew nothing about any shadiness at all.

Ohtani's Friend and Teammate Was Betting With The Same Bookie, Too

Here is a photo of Ohtani with his former Angels teammate and soon-to-be-erased Atlanta Braves player David Fletcher. This was captured from a now-deleted Twitter account.

Fletcher was initially credited with introducing Ippei to Matthew Boyer, Ippei's illegal bookmaker, for the first time at a poker game at a team hotel.

Fletcher later clarified that it was a friend of his who gained Ippei admittance to the now notorious poker game, and that the friend introduced Ippei and Boyer. Fletcher also told ESPN that he never bet with Boyer.

This final statement, apparently, is not true. In May, unnamed sources told ESPN that Fletcher had also bet with Boyer. Those same sources also identified Fletcher's friend from the minor leagues, Colby Schultz, as also being a Boyer customer.

Three days later, MLB told ESPN it was launching an investigation, but was going to have a hard time finding evidence unless the government decides to cooperate with MLB.

The government certainly had no problem cooperating with MLB on the messaging surrounding Ohtani, nor with gassing up the swift go-kart upon which Ippei rode into prosecutorial oblivion.

If Ippei doesn't tell Ohtani that something is going on, the story goes, then Ohtani has no idea it's happening.

This image begins to blur when you realize that Fletcher, described in news reports as "one of Ohtani's closest friends" was doing the same thing as Ippei with the same bookie. Did Ippei – the criminal mastermind behind ordering memorabilia he was planning on fraudulently autographing to his team's own clubhouse under a pseudonym, the man who thought that betting with an underground bookie was legal in California because one time he bet using DraftKings in another state – also manage to silo Ohtani from his good friend? Did Ippei and Fletcher never once discuss their action together?

Some argue this is at least plausible, given this whole story's saving grace: the language barrier between Japanese and English.

We'll explain why this is implausible in a moment.

But first, the framing of the chronicled offenses thus far merits mention.

But, What About The Crime I Didn't Do?

It seems like as soon as new information about this story or its related accusations comes out – Ippei defrauded Ohtani, Fletcher bet illegally, Schultz bet on baseball, Marcano bet on baseball, etc. – it is instantly overshadowed and re-characterized by the fact that whatever the infraction was, at least it wasn't the next worse infraction.

When the full Ippei accusations came to light they were instantly reframed by the qualifiers that Ohtani never bet, never knew about any betting, and that Ippei never bet on baseball. The final assertion came in spite of the fact that it would take a very long time to review 19,000 bets Ippei allegedly made. The veracity of the record-keeping involved is also questionable at best, considering the records came from a low-level runner who flipped.

When ESPN first reported that Fletcher bet with Boyer, it was clarified in the same sentence that Fletcher didn't bet on baseball.

When Schultz was accused of betting on baseball, all his attorneys were left to do was demand a correction from ESPN saying ESPN wasn't trying to imply that Schultz bet using "inside information."

(Leaving aside the curiosity of issuing a correction that confirms that a story did not say something, ESPN did get wrong one element of their reporting: identifying Schultz initially as one of the bookies in Boyer's organization himself.)

These reactions from the defendants are tantamount to your spouse, anticipating you're going to criticize them for something, proactively yelling at you that they're innocent of something else. They are your boss or your creditors, when you hit your quarterly KPIs or fulfill a new business objective, moving the goalposts on you as your review meeting begins.

One does not determine the culpability of a man accused of robbing a convenience store by seizing onto the fact that he did not also assault the cashier.

These types of reactions are occurring for one reason: MLB's chief concern is making sure that when indiscretions do occur, any damage to the public's perception of MLB's on-field product is mitigated or erased entirely.

Belief in the integrity of the on-field product is equivalent to people believing that what they see on the field is legitimate.

If people don't believe that what they see on the field is legitimate, then fewer people will watch, and MLB will make less money.

Everyone around MLB, the players, their attorneys, and those investigating and prosecuting this case, all know this. This is why the framing of the issue, from assertions of victimhood, to no bets on baseball, to the paramount importance of the integrity of the game, is so tightly aligned.

Ohtani Knows Conversational English

The premise of Ohtani never betting, never knowing about his friends' betting, never knowing about fraud, etc., rests on the idea that Ippei single-handedly orchestrated a scheme to perform all the illicit activity himself, hide all the activity from everyone, and isolate baseball's best player from those around him including his agent and financial advisors.

This premise in turn rests on the premise that Ippei was only able to do this because Ohtani only spoke Japanese and Ippei was his only interpreter. Therefore Ippei was the gatekeeper to all of Ohtani's verbal communication.

But it is apparently widely known that Ohtani speaks conversational English.

In this slot machine-nightmare-themed baseball video from a Japanese TV show, Dodgers reporter Kirsten Watson tells the interviewer that she communicates questions to Ohtani in English and that he responds to her in English.

Then there are the overlooked remarks of Fletcher himself from before the time of the affidavit, let alone the plea deal, in which he told ESPN: "We're good friends... We would talk on the bus and at the hotel."

ESPN itself, shortly after the affidavit was released, even highlighted one of the many recorded instances of Ohtani speaking in English and responding to English.

This was all known well before the accusations and affidavit came out. And yet, the collective consciousness just sort of ...forgot about it?

The affidavit notes that Ohtani "does not speak English fluently" and "speaks only limited English at present." It also notes that he did not speak any English at all at the time his bank account was first set up in 2018, i.e., the time during which presumably, either by Ippei's massive cunning or Ohtani's actual insistence, Ohtani was made the sole signer on his own account.

Again, this story has something for everyone: Does "not speak fluently" mean he couldn't understand others around him if they were speaking in English about betting? If you want it to, sure.

Does it mean that Ohtani was solely reliant on Ippei to communicate, and therefore Ohtani never spoke alone with his agent, financial managers and accountants?

Maybe?

The fact that he knew conversational English is particularly damning to one part of the affidavit – the fateful team meeting in Korea when Mizuhara addressed the whole team in English and confessed to an abridged version of the crime he pled guilty to. During this meeting, Ohtani was the perfect amount of in-the-dark.

According to the affidavit.

"No one translated what was said at this meeting to [Ohtani], and he did not understand most of what was said in English, but [Ohtani] was able to understand there was an issue involving [Ippei]. Following the team meeting, [Ohtani] asked [Ippei] what the issue was, and [Ippei] told [Ohtani] that they needed to speak privately.

[Ohtani] and [Ippei] then spoke at the team’s hotel later that evening. During that conversation at the hotel, [Ippei] disclosed to [Ohtani] for the first time that [Ippei] had substantial debts from illegal gambling, and that he had been paying his bookmaker with funds from [Ohtani's] account.

The affidavit didn't need to include the details about when and how Ohtani sort of found out, or didn't find out. But it did. Perhaps to establish the VICTIM's plausible deniability?

Plausible deniability is great.

However, a lot that deniability becomes implausible when you learn Ohtani converses in English.

Money Laundering 101, And Further Suggests Potential Nix/Boyer Connection

One side-wrinkle to the story involves the regulated gambling industry, and draws a long line between casino money laundering, to Boyer, to MLB's investigations of illegal betting activity.

There's a guy named Scott Sibella. If you've never heard of him, you've heard of the casino of which he was president for 8 years: the MGM Grand. Sibella recently pled guilty to charges of failing to file suspicious activity reports (SARs) during his tenure. The Bank Secrecy Act requires casinos to file a SAR for any suspicious transaction that may be relevant to the possible violation of any law or regulation and involves or aggregates at least $5,000 in funds or other assets.

The suspicious activity regarding which MGM Grand should have filed SARs pertained to ... a Southern California illegal bookmaker. But not Ippei's illegal bookmaker, Matthew Boyer. The activity pertained to a different SoCal bookie, Wayne Nix.

Sibella knew that Nix was an illegal bookie, and knew that Nix was wagering with illegally gained proceeds, but he encouraged Nix to patronize the casino anyway.

MGM Grand paid part of a $7.45 million settlement with the federal government to resolve the matter.

After Sibella left MGM Grand, but before he was charged and pled guilty to the property's compliance failings, he took up residency as President of Resorts World Las Vegas just up the road when it opened in 2019.

After the affidavit against Ippei came out, we've since learned thanks to ESPN's dogged reporting that Ippei's bookie, Boyer, was doing the exact same thing at Resorts World that Nix was doing at MGM Grand.

It's a simple, five-step process and should be taught in Money Laundering 101.

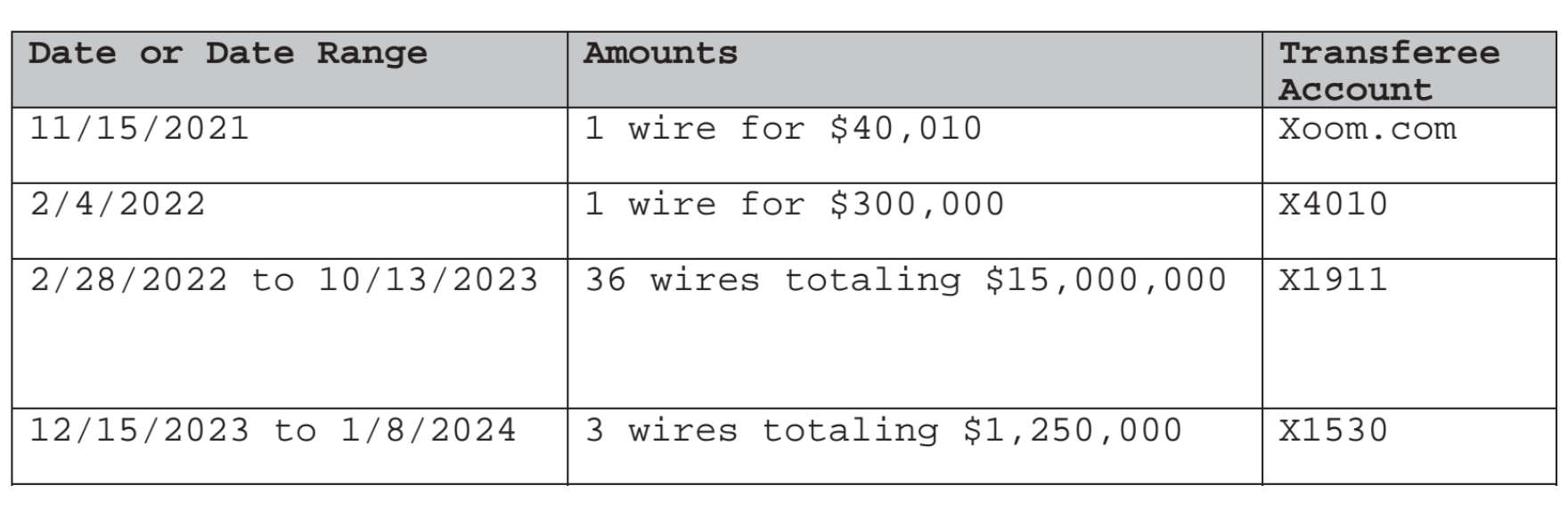

1) Wire illicit proceeds from your illegal gambling business directly to a casino, often millions of dollars at a time

2) Withdraw the money in playing chips

3) Play casino games with some of the chips (inconveniently, you lose a decent amount of the chips you use at this step, but it's the price of laundry)

4) Cash out the remainder of your chips in cash

5) Walk out of a casino with physical cash earned more or less directly from your illegal sports betting operation

So, the criminal activity followed Sibella to his next destination, and was revealed just months after he pled guilty to (and probably felt as if he was putting behind him) the initial incidents at MGM Grand. (Boyer also laundered his proceeds through Pechanga Resort Casino, a massive casino closer to his home in Southern California).

Nothing to date has explicitly connected Boyer and Nix as business partners, but the Washington Post reported in March that federal investigators found out about Boyer's operation through their pre-existing investigation into Sibella and Nix. The same prosecutors who took down Nix, Martin Estrada and Jeff Mitchell, are the ones who handled the Ippei case. (Notably, Boyer has not yet been named in any criminal indictment). Nix and Boyer are both illegal bookmakers from the same area who both laundered their proceeds through the same casino executive's properties, and whose illegal businesses both had deep connections at the employee and customer level to professional baseball.

Along with several other pro sports notables, former Dodgers player Yasiel Puig was Nix's direct customer. Just like federal prosecutors got Ippei not on illegal gambling itself but on bank fraud that fueled illegal gambling and tax fraud resulting from not reporting illegal gambling's proceeds, Puig agreed to plead guilty to lying to investigators about illegal gambling. Puig soon after changed his mind, and then faced obstruction of justice charges.

It all begs the question: Were Nix's and Boyer's operations connected?

The reason to ask this question is to ask what MLB knew, and when.

If Nix and Boyer were connected, then what did MLB learn about others during their investigation of Puig/Nix? Did they learn anything about Ippei? Fletcher? Others? And when did they learn it?

This is not an indictment of MLB. It is instead to explore, if Nix actually is connected with Boyer, how MLB's information gathering in the past several years (and the likely large amount of information they've found that we're not aware of) could have shaped their messaging tactic around the Ippei investigation.

A Brief Pause To Laugh At The IRS

Ippei got rung up on bank fraud and tax fraud. The tax fraud charge alleges he didn't properly report over $4 million in income in 2023.

It's slightly confusing as to what this income is specifically derived from.

The plea agreement says that the unreported income in question is from defrauding Ohtani's bank account, as if to imply that while Ippei was siphoning millions to illegal bookmakers to pay his gambling debts (see below), he also separately siphoned $4 million directly to his own account.

This math doesn't add up, however. Ippei defrauded Ohtani's bank account of $16.9 million. The plea agreement documents all but the small portion he spent on memorabilia as going from Ohtani's account via wire transfer to multiple illegal bookmaker accounts.

One is left to assume that the $4 million in income that hit Ippei's account directly came from his illegal betting winnings (in spite of losing $40 million over 26 months, Ippei still got paid the times he did win).

If this is the case, one might further assume that the plea agreement would say this outright, something like, "Defendant acknowledges that the IRS requires U.S. citizens to report all taxable income, including winnings from illegal gambling, and Defendant admits he earned over $4 million in revenue in 2023 from illegal gambling that went unreported on his tax return."

Regardless, was Ippei truly supposed to declare $4 million in illegal gambling winnings on his taxes? Mais oui.

As always, it's worth taking a moment to remind ourselves of one of the more absurdist enforcement tricks up the U.S. government's sleeve (shout out U.S. v. Sullivan).

The IRS' internal dialogue goes like this: If you have obtained income through illicit means then you or others are guilty of a crime and we'll come after you.

But if we can't get you that way, we have another way: when you don't report that illegal gambling income on your tax return, that's also a crime, and we'll come after you for that.

In other words: You're not supposed to do the activity, but if you do, we'd better get a cut!*

In fact, when the IRS reminded filers of this policy on their website earlier this year, a screencap of it went viral.

Don’t forget to report your income from illegal activities and stolen property as you’re doing your taxes this year pic.twitter.com/txjaeEMqAV

— greg (@greg16676935420) February 19, 2024

*But of course, this isn't about the government getting its cut. Ippei was an eye-watering $40 million in the hole, clearly losing far more than he won. Had he filed correctly, he would've itemized his losses, which would have vastly outweighed his winnings, in which case he would have paid little to zero tax. This is about being able to identify criminal activity and find other creative ways to prosecute criminals.

How Is Ohtani Not Also Guilty Of Tax Fraud?

Ippei's plea agreement says that Ippei knowingly lied when he told others in Ohtani's circle that Ohtani wanted his player salary bank account (the one Ippei defrauded) kept private from anyone else's visibility. This is insane on its face because that's not how accountants or financial managers operate. But setting these professionals' alleged negligence aside, this raises two questions.

First, if Ippei's conviction related to tax fraud is because he didn't accurately report his taxable income, how is Ohtani not guilty of the same crime? We are to believe that no one other than Ohtani, who never checked the account, and eventually Ippei, who fraudulently accessed the account merely to drain it, had access to Ohtani's salaried account for a six year period. The reasons we are to believe this are:

1) The financial managers in the affidavit all attested that they didn't have access to the account.

2) Ohtani is listed in the affidavit as being the only signatory on the account, and therefore, aside from Ippei, being the only person with visibility into the account.

3) Ohtani clearly never once looked at the account in question from late 2021-onward, because if he had he would've seen $500,000 wires fleeing out of it faster than schools fleeing the Pac-12.

4) At no point in any of the presented evidence has it been alleged that Ohtani signed over account access to anyone, and then subsequently restricted that account access again. In fact, if you believe Ippei, Ohtani wanted the account made private from the very first day it was set up in 2018.

Ohtani earned some $42 million in salary and bonuses over those 6 years, $30 million of which came in 2023.

How did Ohtani report his taxable income if no one ever looked at the account?

Did anyone even check his W2s? Are we sure the Angels deducted the right amount of tax from Ohtani's massive paycheck each year, down to the cent?

Even though Ippei was draining the account like he was planning a rich heiresses wedding (see below), did the millions funneling through the account ever generate any interest income?

The timeline of this tax negligence existed for several years prior to Ippei beginning to defraud Ohtani's account.

We're having a hard time seeing how Ippei didn't just plead guilty to a crime of which the person he defrauded is himself guilty.

It's Plausible That Ohtani Did Want His Salary Account Kept Private All Along

Second, the totality of the evidence suggests that Ohtani genuinely did want to keep his own salaried account private. Yet, the factual basis established in Ippei's own plea agreement suggests that somehow this isn't true.

From the plea agreement (underline added):

When [Ohtani's] sports agent and financial advisors asked defendant for access to the x5848 Account, defendant falsely told them that Ohtani did not want them to access to the account because it was private. In truth and in fact as defendant then knew, defendant did not want [Ohtani's] sports agent and financial advisors to review the x5848 Account because he feared they would notice that defendant stole millions of dollars from [Ohtani]. Based on defendant’s false statements of material fact, defendant fraudulently obtained more than $16,975,010 from the x5848 Account.

The fact that Ippei didn't want Ohtani's agents and financial advisors to know he was defrauding Ohtani's account has nothing to do with the veracity of the statement that Ohtani wanted his bank account kept private.

Yes, the criminal compliant notes that Ohtani told investigators in April that in retrospect, he thought his accountants, advisors, etc. had access to all of his accounts all these many years. This to me carries the same weight as, "I know enough conversational English to speak with Americans about fun stuff, but I didn't understand a word of Ippei's confession at the all-staff team meeting where he spoke at great length to stealing from me. And I still didn't understand it when some of the dozens of people who were present tried to explain it to me afterward. I only understood it when I huddled in private with Ippei one-on-one many hours later."

The affidavit notes that Ohtani's account was in fact private from 2018 onward, but it does not say that Ippei set up the account this way without Ohtani's knowledge or blessing. The 37-page document, which of course spares no opportunity to throw Ippei under the bus, has a golden opportunity to allege Ippei deceived Ohtani when setting up the bank account by not providing access to those whom Ohtani wished access. It has a golden opportunity to say that Ohtani asked Ippei to make sure his representatives were on the account.

But it doesn't say that. It just says, "In or about 2018, [Ippei] accompanied [Ohtani] to a Bank A branch in Arizona to assist [Ohtani] in opening the x5848 Account, and translated for [Ohtani] when setting up the account details."

Even if the condition of Ohtani-only access to the bank account was Ippei's idea, it is highly unlikely Ohtani didn't know that Ohtani was the only signatory.

Are we truly to believe that Ippei sat with Ohtani in the lobby of a Phoenix, Arizona, Bank of America in 2018 and concocted the mother of all "long games," saying to himself:

- I think three or four years from now I might want to defraud my best friend and lifetime meal ticket

- My best friend wants several of his accountants, financial advisors etc., to be signers on his account. I'm going to tell my best friend in Japanese, while sitting right in front of this English-speaking personal banking representative, that they're all going to be made signers, no problem

- But in truth, I'm going to tell this English-speaking personal banking representative, right in front of my Japanese-speaking best friend, that Ohtani wants himself to be the only account signer, and that's how it's gonna be

- The accountants and financial advisors will never once in the coming years ask my best friend directly why they have no direct visibility into his account. I'll make sure they never once talk to him without me present! And my best friend will never once attempt to check his account that only he has access to and that I will eventually lock him out of. This will work!

- Since I'm deceiving my best friend right now anyway, I could go ahead and secretly make myself a signer on his account too, since my best friend is very aloof and doesn't know what's going on. This will really help with all the frauding I intend to do later on

- But I won't do this. This would be too simple. Instead, when I want to defraud him several years from now, I'll also commit bank fraud: I'll change his online credentials, then call the bank and impersonate him to give vocal authorization to an insane number of wire transfers over and over again

If you do not believe this happened, then it's plausible for you to believe that Ippei was acting in something close to good faith when he set up the account.

Why would Ippei have begun deceiving Ohtani in March 2018 at the point of bank account creation, when such actions would provide no benefit to Ippei until four years later when, like the flip of a light switch, he decided to start betting $300,000 a day and needed a source to fund it? If defrauding Ohtani was Ippei's plan all along, Ippei would've made himself a signer on day 1, and wouldn't have started trying to pay off his gambling debts through several other means before settling on wires from Ohtani's account.

If Ippei was acting in good faith when he set up the account to have Ohtani-only access, then Ohtani likely wanted his account set up that way, or at least knew it was being set up that way and didn't object.

If Ohtani didn't want the account set up that way, then he would've at some point, you know, cared. He would've inquired as to who could access his account, mandated that he meet with his accountants, etc.

Thus, what is Ippei attesting that he lied about?

The only way Ippei can appeal his plea deal is if he argues that he didn't plead guilty voluntarily.

Imagine that.

Why Are We Talking About Dentistry?

One of the critical details of Ippei's original story to ESPN (which Ohtani's own publicists greenlit) and to the Dodgers organization, was that Ohtani agreed as a good friend to pay off Ippei's gambling debts.

Of course, when news of these initial assertions leaked, which could have made Ohtani culpable, about 71 attorneys hit the record scratch button and changed the prevailing narrative to: Ohtani knew nothing and blessed no such payments.

The plea agreement does note that Ohtani agreed to fund other purchases that Ippei couldn't afford, like massive amounts of dental work. From the plea:

[Ohtani] agreed to pay for defendant’s dental work and authorized a check to defendant for $60,000 drawn on [a different account from the one Ippei defrauded]; however, without permission or authorization, defendant provided his dentist with [Ohtani's] debt card number for the [account that Ippei defrauded] and charged $60,000 to the account. After defendant paid his dentist with [Ohtani's] debt card, defendant then deposited the $60,000 check from [Ohtani] into defendant’s personal checking account for defendant’s personal use.

Setting aside the obvious jokes about Ippei needing the expensive dental work because his face was taking turns being used as a punching bag by Boyer's goons and by Rob Manfred's goons, why are we talking about this and why would Ippei do this?

If Ippei had already stolen $16 million from Ohtani through a foolproof method, why would Ippei go to all the trouble of asking Ohtani for a check? Why wouldn't Ippei just continue to use the foolproof method?

Plus, why is Ippei asking Ohtani for a personal favor so that he can steal another $60,000? Ippei was an extra $24 million in the hole with Boyer. What is $60,000 going to do?

Does any of this really matter in terms of establishing Ippei's character as devious and dishonest? There's ample evidence for establishing that already. When you say someone stole $16 million to bet with, spent $300,000 a day, and was $40 million in debt, adding in that the victim was actually willing to pay his defrauder $60,000 in dental expenses and then the defrauder stole another $60,000, seems like minutae. Yet, the U.S. attorney's office couldn't resist highlighting it in their press release regarding Ippei's agreement to plead guilty.

This is tantamount to prosecutors including in the affidavit text messages from Boyer to Ippei saying that Ippei didn't steal money from Ohtani, and the prosecutors acting as if this statement supports their case.

All the inclusion of this seems to illustrate is that Ohtani was willing to pay for some of Ippei's expenses, which just brings back to mind Ippei's initial interview with ESPN and what he first told the Dodgers, which there was a coordinated effort by all to erase from the public record.

Ippei Pleads Guilty, Further Scapegoats Emerge

June 4th was a very important day for the MLB PR engine, which, unlike Ohtani's publicists, actually knows what it's doing.

It was on this day that Ippei formally pled guilty in court. He will be sentenced in October. He will likely serve jail time.

(One metaphorical and actually very sad form of sentencing came when Ippei was fired just a few days later from Uber Eats as a delivery driver, because apparently he was also working for Uber Eats the past several years?).

The media coverage around the court date was used by the prosecution and Major League Baseball as yet another opportunity to hit all of their desired (integrity-salvaging) talking points. It was choreographed better than Swan Lake.

- From Estrada: "Mr. Ohtani is an immigrant, came to this country, is not familiar with the ways of this country, and therefore was easily prey."

- From MLB: "MLB considers Shohei Ohtani a victim of fraud and this matter has been closed."

- From the MLB.com article about the guilty plea: "'I want to emphasize this point: Mr. Ohtani is considered a victim in this case,' U.S. Attorney Martin Estrada said during an April news conference."

- From Ohtani, back to his pretty-good-English levels: "This full admission of guilt has brought important closure to me and my family."

You might think, enough already, we covered this. Everybody already took victory laps the moment the affidavit was released, and again the moment the news broke that Ippei would plead guilty. Why are you telling me for a third time how much of a victim Ohtani is? Isn't it in Ohtani and MLB's interest to stop talking about this, and for this story to go away?

It isn't, actually, when you realize the purpose of June 4th was to facilitate the Reverse Compliment Sandwich we referred to at the beginning of this piece.

June 4th was also the day that MLB decided to hit Tucapita Marcano, a player in the Pirates and Padres organizations, with a lifetime ban for betting on baseball. It also served shorter punishments to four existing minor league players. There was no time for people to marinate on the fact that, holy shit, baseball players are betting on their own teams. You didn't even hear about what Marcano did past one sentence, because the entire story became about how swift and decisive the punishment was.

These punishments came by virtue of evidence that MLB's Investigations Department sourced themselves, not from existing criminal investigations. Conveniently, these players' betting activity was done in the legal market, meaning that MLB's sports betting partners at least had a shot of identifying and reporting the activity.

Serving these punishments in virtually same breath as the Ippei final hammer helped feed a whole bunch of fresh meat to the hounds of justice. MLB is tough on crime! Our game isn't compromised – we root out the corruption! See?

The Ippei-Marcano one-two punch formed the two strong slices of bread in the sandwich.

But what was between the two slices?

That fact there is likely an ongoing criminal investigation into the full extent of Boyer's operations that hasn't even come to light.

The fact that the David Fletcher investigation into him betting illegally is just beginning.

The fact that so much of this still makes no sense.

The fact we will likely never know anything even close to the full truth.